COVID Disruptions to the Rental Housing Sector in Canada's Major Metros

February 26, 2021

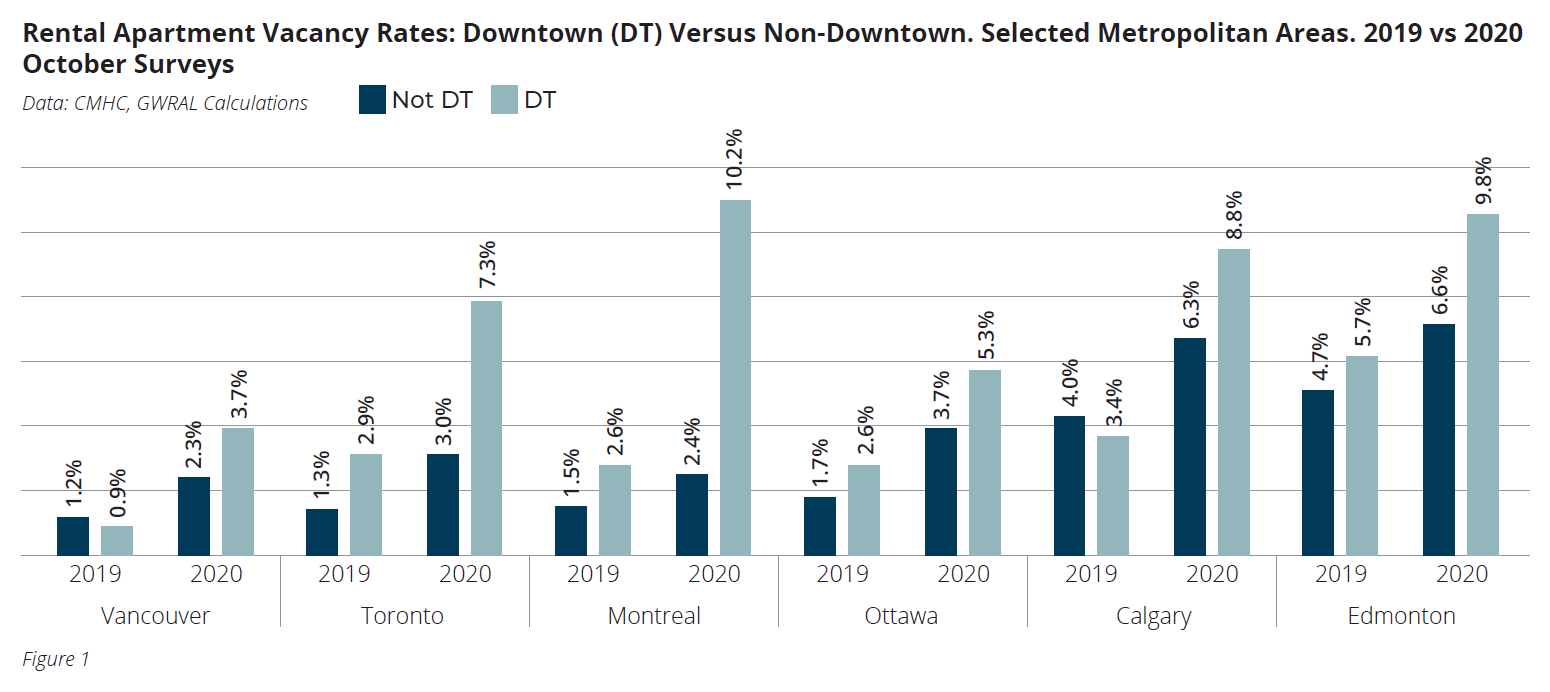

Purpose-built rental apartment vacancy rates across Canada increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the downtowns.

This was not primarily from an exodous of renters. New supply drove most of the vacancy growth as occupancy levels stayed reasonably stable or even grew across major markets, according to the latest CMHC data. COVID-19 restrictions resulted in a lack of domestic and international migration, which these markets typically rely on to fill new or vacated rental units.

Downtown-area rental housing is particularly dependent on a flow of newcomers. In normal times, Canada’s major cities see a continual stream of domestic and international migrants—approximately 75% of whom rent upon arrival (based on the last 2016 census). Newcomers to the major metros tend to

be younger adults between age 19 and 34—also a prime renter demographic.

This cohort also often choses to rent in the downtowns, attracted to the vibrancy of the city as well as the proximity to jobs and transit. As they often have limited possessions and are in single- and two-person households upon arrival, smaller units suit them.

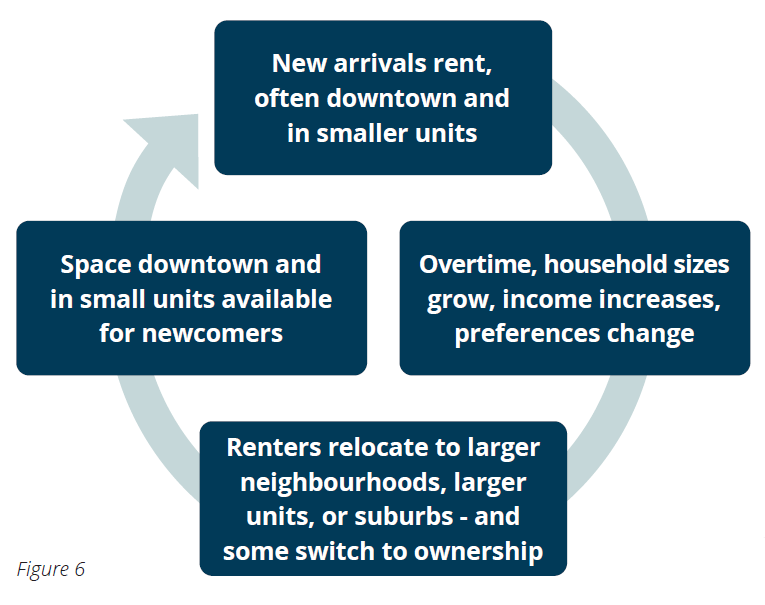

Over time, those who stay in the region, will often gradually move on to other housing options, whether larger units or rental elsewhere in the metro area, or even ownership (See Figure 6 page 4). This latter phenomenon of moving on continued during COVID-19, and likely even temporarily increased as renters sought more space for sheltering in place—or lower rents for equivalent homes—further from the core. Some households likely took advantage of historically low mortgage rates and shifted to ownership sooner than they otherwise would have done.

Once more normal population flows and downtown life returns, GWLRA is confident that renters will also again flock to the smaller units and downtown core. Below are more details on specific markets.

Toronto

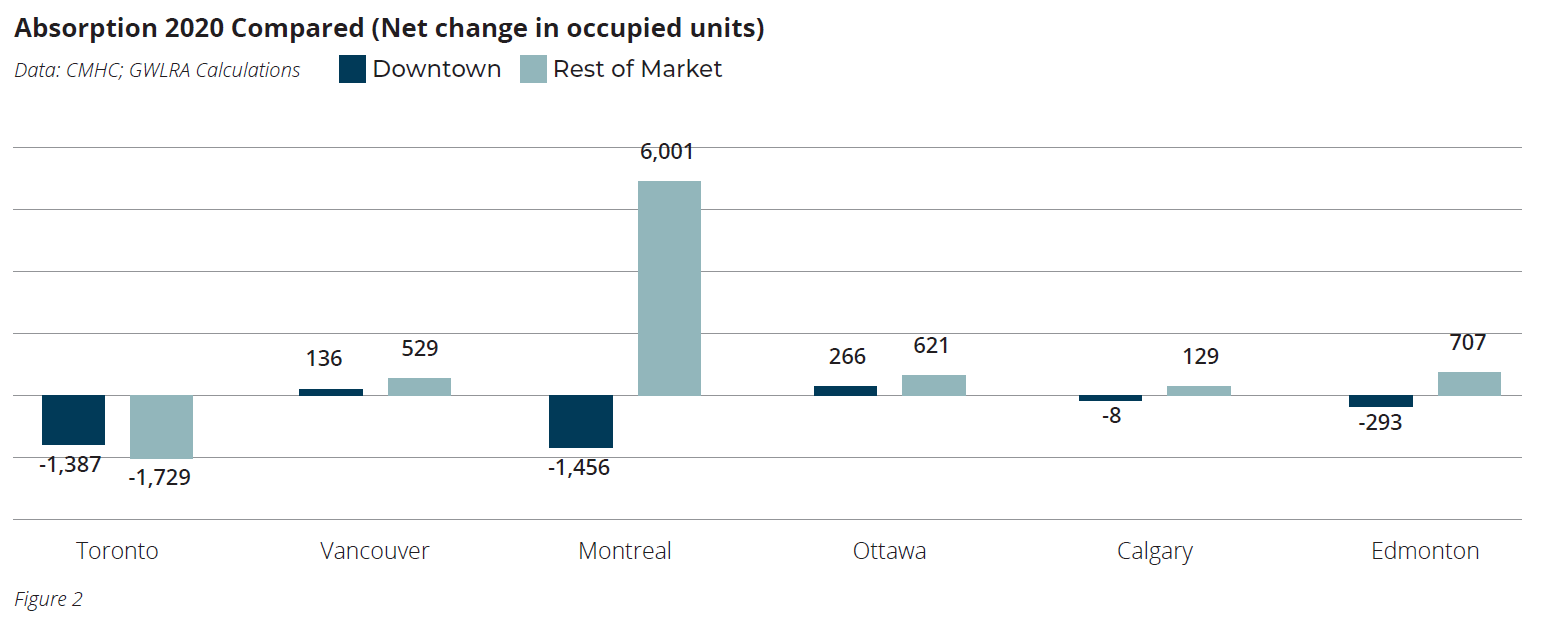

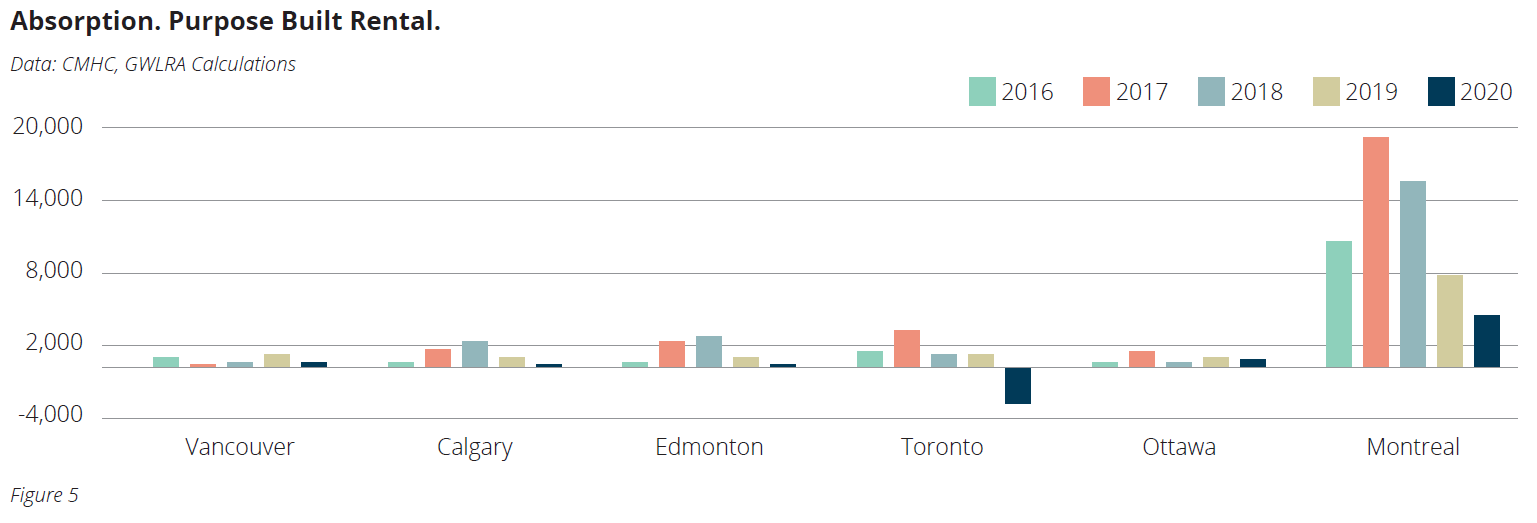

Toronto, had a small negative absorption of 3300 units between downtown and the rest of the metro area (out of an inventory of 320,000) in 2020. This was the only major metropolitan area to experience a decline in occupied purpose-built rental units.

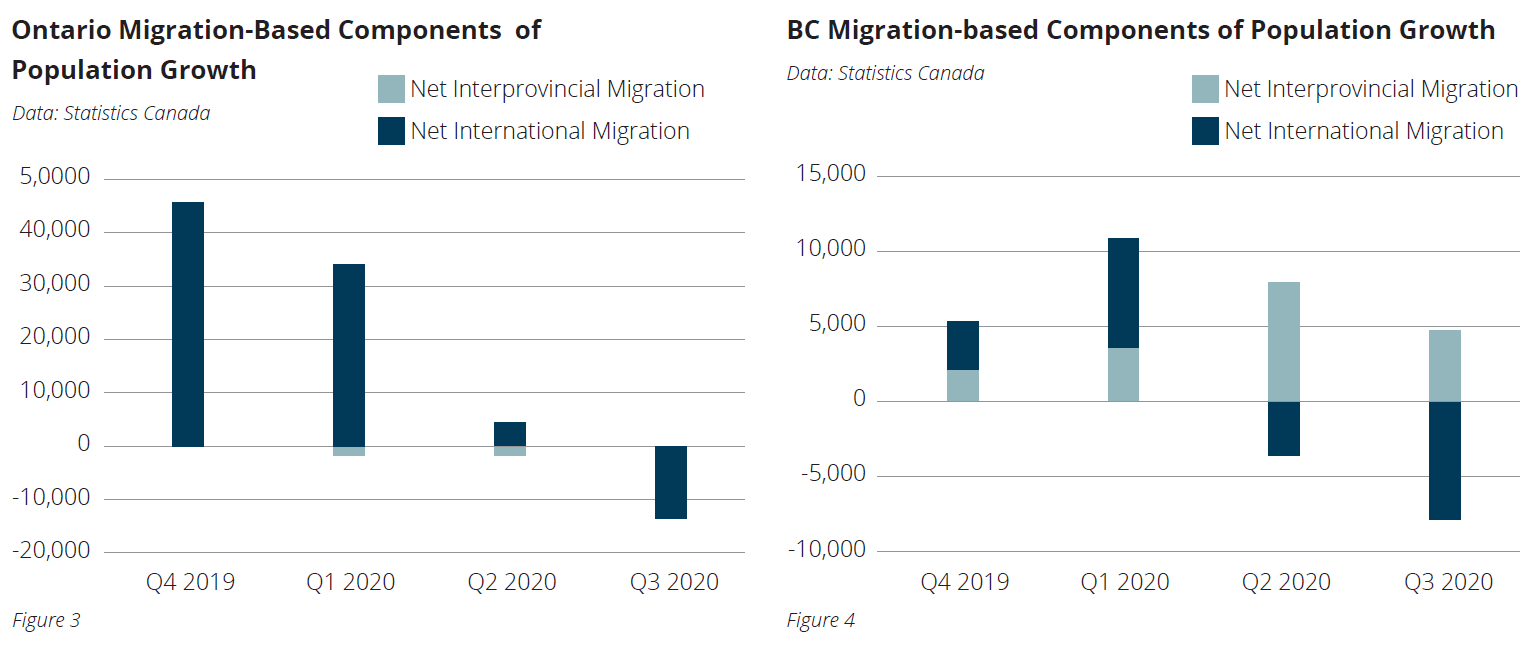

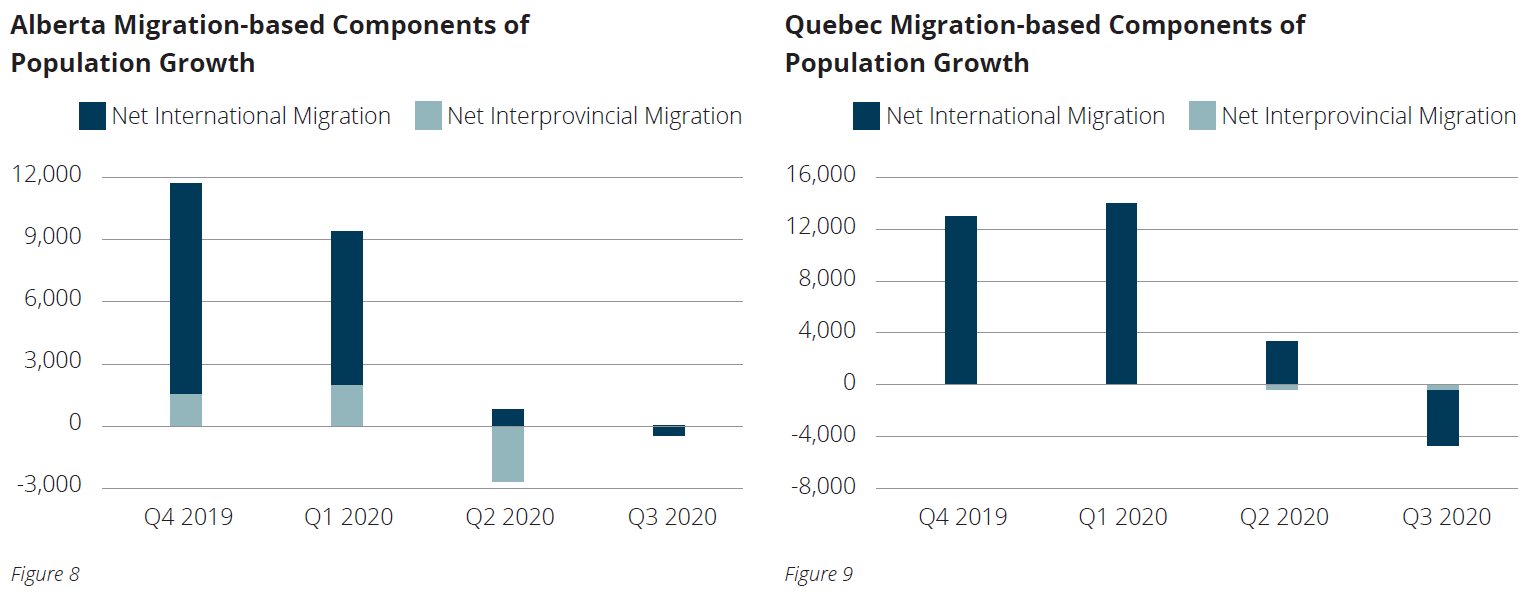

The GTA may have been hardest hit in terms of population flow. Although we will not have COVID-19-related population change estimates at the metro-area level from Statistics Canada until 2022, the net population outflow from Ontario through Q3 2020 is an indicator (see Figure 3). Also, some renters may have switched to the shadow market (rental condos), which itself likely had a boost in supply, as a result of shorter term rentals being returned to the long-term rental market and some condo owner-occupiers relocating (temporarily?) outside their regions, able to work from anywhere.

The condominium supply experienced rental rate declines ranging from 21% for studio suites to 13% for two bedrooms, although only 2% for 3 bedroom homes (Urbanation). The fact that Condo owners needed to reduce rates this substantially illustrates the over supply and softer demand for rental condos.

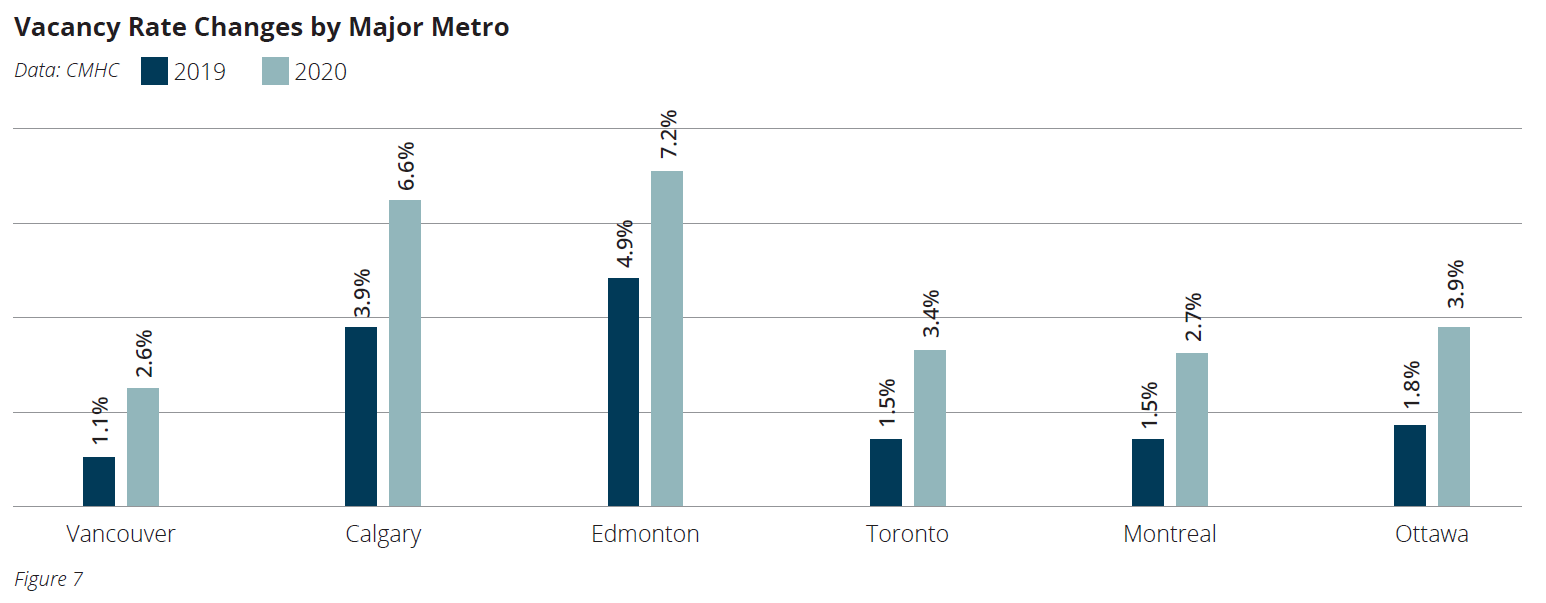

Purpose-built rental remained well occupied with the overall vacancy rate at 3.4% (Figure 7)—a further sign that renters prefer purpose-built when they can find equivalent product.*

Once normal domestic and international population flows return, likely in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022, the vacancies should fill quickly in Toronto, which in recent years has received as much as 37% of Canada’s annual immigrants. Should the government’s new annual target of 410,000 (or more) be reached, this could bring as many as 150,000 international arrivals to Toronto each year if this ratio holds.

Vancouver and Ottawa

For Vancouver and Ottawa there was positive absorption in the downtowns and overall alongside a wave of new purpose built supply. The new buildings drove up vacancy rates. The Downtown Peninsula of Vancouver (which we calculated to include the West End and Yaletown) went from 0.9% to 3.7% vacancy and Ottawa’s downtown vacant units expanded from 2.6% to 5.3% of the market. Vancouver’s rental demand may have had modest support from positive inter-provincial migration, assuming some of the net newcomers to BC settled in Vancouver (See Figure 4). The higher ownership prices also likely kept more households renting than elsewhere in Canada.

Montreal

In Montreal, new supply as well as a modest net-outflow of renters pushed the vacancy rates downtown higher, from 2.6% to 10.2%. The overall market experienced 4,500 units of absorption, on the strength of demand in Boucherville/Brossard, Beauharnois, Blainville, and Chomedey. While this was more than any other market, these 4,500 units of net absorption was substantially down from recent trends. See Figure 5.

Calgary and Edmonton

Meanwhile in Alberta, Calgary had a statistically-flat negative 8 units of absorption downtown and Edmonton negative 293. However, in aggregate rental demand increased in both cities alongside a rise in supply. The uncertain economy and downward-trending housing market has also been a tailwind for rental demand in Alberta’s cities. Many renters are unsure if they will stay in the region long term; and there is no risk of missing out of opportunities to own by delaying purchase. It is noteworthy that despite the extra economic challenges Alberta faces in addition to COVID-19, the net population flow was flat in Q3 (see Figure 8). Cheaper rental and ownership housing likely played a role in retaining some residents and attracting others able to work from anywhere.

Suburbs

In all metro areas, positive absorption was most pronounced in certain suburbs. New Westminster and the Tri Cities had strong growth in Vancouver (all urban-suburban with rapid transit to downtown). Meanwhile less-urban Pickering had the strongest absorption in the Toronto area. Some of this may be pandemic related. Renters working from home or with a reduced income likely wanted to save money or obtain a larger rental home; moving further from the downtown would facilitate this. Post pandemic, we anticipate less rental demand growth in more distant locations like Pickering; however the transit-oriented, amenitized inner suburbs such as New Westminster may see continued stronger interest from renters.

Conclusions

COVID-19 disrupted normal population flows that support the rental housing sector. Once the COVID-19 risk is substantially reduced, likely later in 2021 and into 2022, GWLRA has confidence that the normal patterns will return when it comes to downtown demand. We also believe that future demand growth may become slightly more evenly spread between the downtowns and other urban and urban-suburban regions; if renters can work from home some of the time, they may be more tolerant of a crowded subway or congested vehicle commute than they were pre-pandemic and choose to live further from their jobs.

Leading the national Research and Strategy team, Wendy’s responsibilities include providing economic, demographic and market-trends analysis to support long-term asset acquisition, development and management strategies. Wendy has been working in real estate research since 2002, including over a decade with GWL Realty Advisors. She holds a Ph.D. in comparative-world and economic history from the University of Arizona.